Doing some research the other day on F.W. Norwood I came across this article from the New York Times of October 1922. I've cut out a few paragraphs about Jefferson's opinion of the church in England, so if that interests you here's a link. What I find interesting about this article - and with the article I last published - is how similar the rhetoric is to the tradition of European peace orations that stretches back to the renaissance. Particularly surprising in this instance was the reference to "The Turk"trampling Europeans unresisted and burning Smyrna. This event ended several years of war between Greece and Turkey in September 1922, only a month before this interview was published.

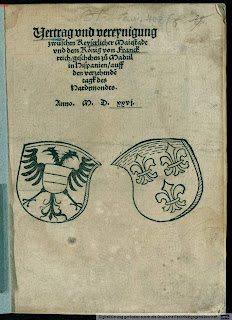

It was certainly topical, but it also drew upon much older ideas. For instance, I'm reading a few orations from the mid-sixteenth century by French humanists who refer to very similar issues in reference to the east, the need for Christians to behave in a way that their faith suggests and the benefits or limits of pacifism. I'll put those texts and my conclusions up here when I'm done.

Apart from that, I think it's a interesting period piece about American perceptions of inter-war Britain. A brief biography on Jefferson can be found here, and here's a link to Jefferson's original sermons on peace.

AMERICAN VISITOR FOUND ENGLISH BENT ON PEACE

29 October 1922.

THE Rev. Dr. Charles E. Jefferson is attracting congregations on Sunday evening to the Broadway Tabernacle, Fifty-sixth Street and Broadway, with stories of his recent visit to England in an exchange of pulpits with the Rev. Dr. F.W. Norwood of the City Temple, London, and as preacher in other leading British Free Churches.

“I went to see the things that were lovely and of good report,” he said, “and that is what I saw,” Dr. Jefferson added that he liked England because it is a land where people are well bred; he liked London because it is old and quiet; the British “bobbies” because they are policemen who never lose their tempers; the crowds because they are orderly and good natured; the quaint old-time names of the London streets – the Poultry Cheapside, Shoe Lane and Plumtree Court – the devotion and attention and punctuality of British congregations and their fervent singing, and the affection displayed by the people for their King and Queen and the Prince and Princess of Wales. Altogether, he confessed that he had a visit charming in every way.

“Great Britain and America must be friends,” said Dr. Jefferson, “Without co-operation they cannot take action or any definite policy; united they can. For example, together they could help France or Italy or Russia do the right thing. A useful work is done in that direction be the interchange of preachers, politicians, journalists, bankers and business men.”

Dr. Jefferson saw Lloyd George at a luncheon and came to the conclusion that he possessed the four qualifications required for a war against war – knowledge, experience, conviction and religion.

“My! the English are interested in politics!” he exclaimed, smiling at the rememberance. “They are very much alive. They have suffered by the late war and are in no mood for another. The politicians know this and will go very carefully for some time.

“The people are more interested in the question of the church’s views about war than they are here. Ministers declare that the churches must take a stand. They are going in the direction of the extreme pacifist position, but I do not know that they would go all the way if you pinned them to a concrete case.

“There is no common understanding among Christians as to what is the Christian attitude on war. Some think that it not the Christian thing to let the Turk trample on us and burn Smyrna. They wonder whether it is not the Christian thing to kill him. The same people who took part in the ‘No More War’ procession in London would, I imagine, adopt that view if they had to decide one way or the other.

“The tragedy is that we Christians get together and enunciate Christian principles, but at that the same time the men who direct policy – the rulers, the politicians and journalists – are busy planning another course, and when war comes the churches are swept into it.”

Changing the subject, Dr. Jefferson said:

“Many British homes are surrounded by gardens and the gardens by hedges. The Britisher retires to his home and his garden and builds up a hedge of reserve about himself. He is a good fellow when you get to know him, but it takes time to do that.

“On my two previous visits to Britain I went as a tourist, and I never learned much about the true Britain. This time the hedges were down and I was admitted to intimacies hitherto unrealized. Everywhere I was received with the greatest courtesy. The first English home offered to me was an Anglican home. That pleased me very much. Attempts were made to obtain an Anglican pulpit for me in which I might preach, and I would like to have done so, but my program had been fully arranged. On epulpit was offered, but a precious engagement prevented my acceptance….

Newpapers and newspaper men next came up for consideration.

“I think the English newspapers are fine, and are served by able men,” he said. “The editorial pages were a delight to me. I noticed there was a much more friendly attitude to Americans than ten years ago.

“There is much more news of Europe in American papers than of America in British papers. I wish that news about the worst side of American life was not cabled across to the extent that it is. Such news must give English men quite the wring impression of America. For the first two weeks I felt ashamed to hold my head up as an American in view of what was being recorded in the papers at the time. I do not see why the underworld of New York should be raked up. Every city has its underworld.

“There are more murders and divorce cases in British papers than there used to be, and newspaper men themselves do not think that the papers are so good as ten years ago. Journalists can do much better to foster friendly relations between the two English-speaking countries, and the interchange of journalists is contributing toward this end.’